Understanding Texas Cattle Fever: History, Causes, and Impact. Sound Familiar, Bird Flu, Covid, Measles, Polio, Whooping Cough..etc.?

By: Tamara Miner Haygood, Published: 1952, Updated: May 17, 2017. The TV series Yellowstone was based on this story, more than the second 1883 than the modern one.

A Texas Longhorn Cow. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

The yearly Cattle Drive of the Longhorn cattle out of Texas proved that they were immune to the disease they carried. This wiped out the cattle herds that the Trail drivers used. Cattlemen along the route fired on the drivers. To drive them off, so their cattle, who were not immune, like the Longhorns, which had developed Natural Immunity.

Map of the spread of Cattle Fever, 1902. The land south of the black line was infested with the cattle tick. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

Local Cattle ranchers thought the disease was caused by the ever-present ticks.

Cattle Ranchers started to lose whole herds, then their ranches, as most were mortgaged to a bank.

Diagram of the spread of Cattle Fever through ticks. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

A Cow sick with the Fever. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

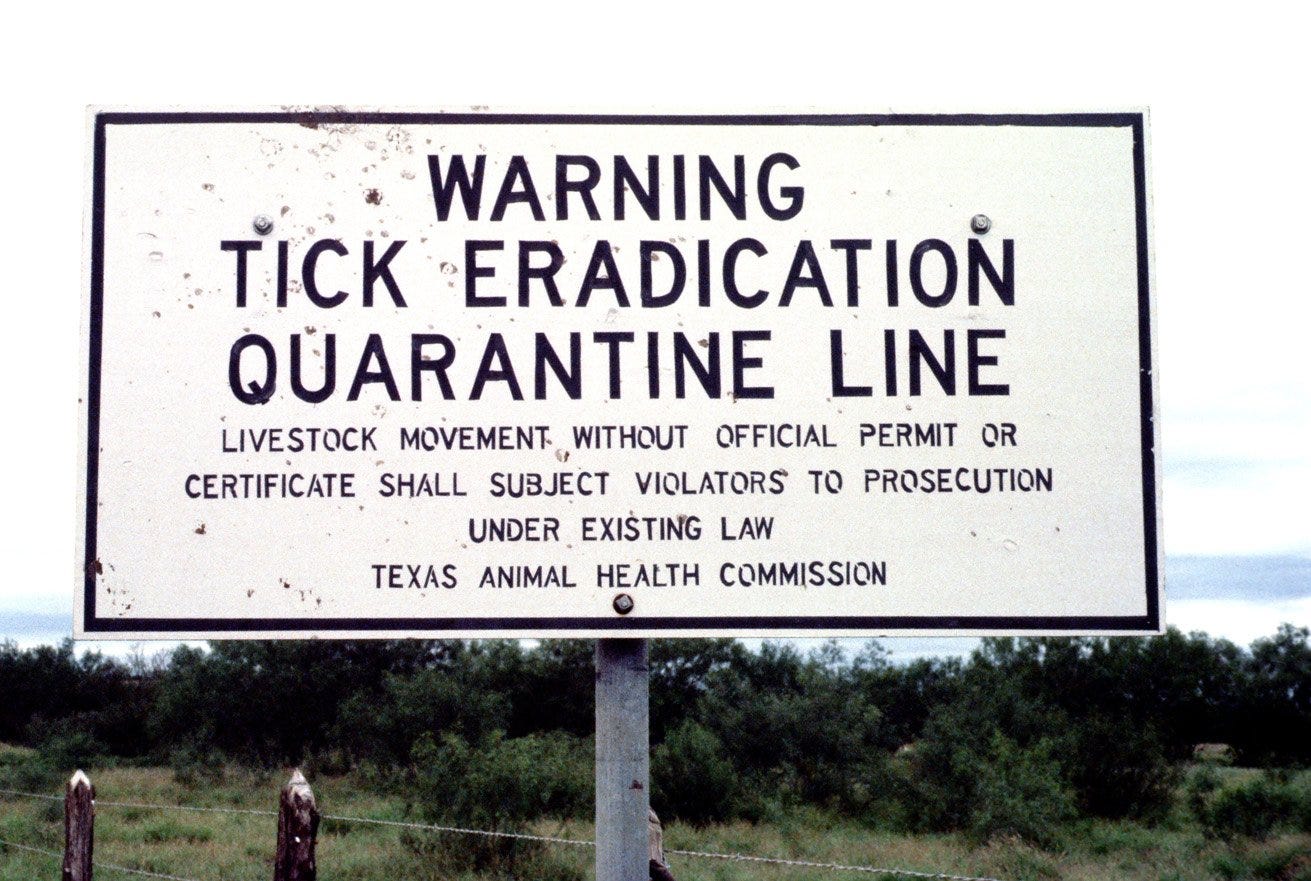

Texas Fever: Readers of the Veterinarian, an English journal, were informed in June 1868 that a "very subtle and terribly fatal disease" had broken out among cattle in Illinois. The disease killed quickly and was reported to be "fatal in every instance." The disease was very nearly as fatal as the Veterinarian claimed. Midwestern farmers soon realized that it was associated with longhorn cattle driven north by South Texas ranchers. The Texas cattle appeared healthy, but midwestern cattle, including Panhandle animals, allowed to mix with them or to use a pasture recently vacated by the longhorns, became ill and very often died. Farmers called the disease Texas fever or Texas cattle fever because of its connection with Texas cattle. Other names included Spanish fever and splenic or splenetic fever, from its characteristic lesions of the spleen. The disease is also known as hemoglobinuric fever and red-water fever, and formerly as dry murrain and bloody murrain. To protect their cattle, states along the cattle trails passed quarantine laws routing cattle away from settled areas or restricting the passage of herds to the winter months, when there was less danger from Texas fever. In 1885 Kansas entirely outlawed the driving of Texas cattle across its borders. Kansas, with its central location and rail links with other, more northern markets, was crucial to the Texas cattle-trailing business. The closing of Kansas, together with restrictive legislation passed by many other states, was an important factor in ending the Texas cattle-trailing industry that had flourished for twenty years (see SHAWNEE TRAIL).

The Shawnee Trail: A Historical Route for Texas Longhorn Cattle.

The Shawnee Trail: A Historical Route for Texas Longhorn Cattle. The principal routes by which Texas longhorn cattle were taken afoot to railheads to the north, the earliest and easternmost was the Shawnee Trail. Used before and just after the Civil War, the Shawnee Trail gathered cattle from east and west of its main stem, which passed through Austin, Waco, and Dallas. It crossed the Red River at Rock Bluff, near Preston, and led north along the eastern edge of what became Oklahoma, a route later followed closely by the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad. The drovers took over a trail long used by Indians in hunting and raiding and by southbound settlers from the Midwest; the latter called it the Texas Road. North of Fort Gibson the cattle route split into terminal branches that ended in such Missouri points as St. Louis, Sedalia, Independence, Westport, and Kansas City, and in Baxter Springs and other towns in eastern Kansas. Early drovers referred to their route as the cattle trail, the Sedalia Trail, the Kansas Trail, or simply the trail. Why some began calling it the Shawnee Trail is uncertain, but the name may have been suggested by a Shawnee village on the Texas side of the Red River just below the trail crossing or by the Shawnee Hills, which the route skirted on the eastern side before crossing the Canadian River.

Shawnee Trail Sculpture in Frisco. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

Texas herds were taken up the Shawnee Trail as early as the 1840s, and use of the route gradually increased. But by 1853 trouble had begun to plague some of the drovers. In June of that year, as 3,000 cattle were trailed through western Missouri, local farmers blocked their passage and forced the drovers to turn back. This opposition arose from the fact that the longhorns carried ticks that bore a serious disease that the farmers called Texas fever. The Texas cattle were immune to this disease; but the ticks that they left on their bedgrounds infected the local cattle, causing many to die and making others unfit for marketing. Some herds avoided the blockades, and the antagonism became stronger and more effective. In 1855 angry farmers in western and central Missouri formed vigilance committees, stopped some of the herds, and killed any Texas cattle that entered their counties. Missouri stockmen in several county seats called on their legislature for action. The outcome was a law, effective in December of that year, which banned diseased cattle from being brought into or through the state. This law failed of its purpose since the longhorns were not themselves diseased. But farmers formed armed bands that turned back some herds, though others managed to get through. Several drovers took their herds up through the eastern edge of Kansas; but there, too, they met opposition from farmers, who induced their territorial legislature to pass a protective law in 1859.

During the Civil War the Shawnee Trail was virtually unused. After the war, with Texas overflowing with surplus cattle for which there were almost no local markets, pressure for trailing became stronger than ever. In the spring of 1866 an estimated 200,000 to 260,000 longhorns were pointed north. Although some herds were forced to turn back, others managed to get through, while still others were delayed or diverted around the hostile farm settlements. James M. Daugherty, a Texas youth of sixteen, was one who felt the sting of the vigilantes. Trailing north his herd of 500 steers, he was attacked in southeastern Kansas by a band of Jayhawkers dressed as hunters. The mobsters stampeded the herd and killed one of the trail hands; (some sources say they tied Daugherty to a tree with his own picket rope, then whipped him with hickory switches.) After being freed and burying the dead cowboy, Daugherty recovered about 350 of the cattle. He continued at night in a roundabout way and sold his steers in Fort Scott at a profit. With six states enacting laws in the first half of 1867 against trailing, Texas cattlemen realized the need for a new trail that would skirt the farm settlements and thus avoid the trouble over tick fever. In 1867 a young Illinois livestock dealer, Joseph G. McCoy, built market facilities at Abilene, Kansas, at the terminus of Chisholm Trail. The new route to the west of the Shawnee soon began carrying the bulk of the Texas herds, but the Shawnee Trail continued to supply cattle to processing plants and the path was mirrored by the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad.

Though Texas fever was clearly associated with Texas cattle, its cause remained for many years a mystery. Various theories were proposed to account for a fatal disease being transmitted by apparently healthy animals. One held that the longhorns ate poisonous plants (Loco Weed) that did not hurt them but that made their wastes so toxic that the smallest amount accidentally ingested by a nonimmune midwestern cow could cause illness and death. By the 1880s the work of pioneer bacteriologists Robert Koch of Germany and Louis Pasteur of France, among others, was widely known and accepted. These men had identified several specific disease-causing bacteria, and Pasteur had devised vaccinations to prevent chicken cholera and anthrax. Hoping for similar success, scientists studying Texas fever also were looking for a microorganism. In 1893 Theobald Smith and Fred Lucius Kilborne of the federal Bureau of Animal Industry in Washington, D.C., announced their isolation of the pathogen of Texas fever. They demonstrated that the disease is caused by a microscopic protozoan that inhabits and destroys red blood cells. Smith and Kilborne named the protozoan Pyrosoma bigeminum. It is now recognized that either of two species of the renamed genus Babesia, called Babesia bigemina and Babesia bovis, may be involved in Texas fever. From this is derived the modern name babesiosis, which is applied both to Texas fever and to infections caused throughout the world by these pathogens and other members of the same genus. Besides identifying the microorganism responsible for babesiosis, Smith and Kilborne discovered that the disease was spread by cattle ticks. After sucking blood from an infected animal, a tick would drop off into the grass and lay eggs from which would hatch young ticks already harboring the protozoan. Weeks after the original tick dropped from its longhorn host, its progeny were still capable of infecting other cattle. Several different species of tick are now known to spread babesiosis.

Identification of the pathogen and vector of babesiosis still did not explain the apparent good health of the Texas cattle that carried the disease. Modern research indicates that calves are born with a natural partial resistance to infection that lasts a month or two after birth and goes away gradually. In areas like nineteenth-century Texas (and other southern states), where the disease was widespread, the calf suffers a mild attack at an early age, then develops enough immunity to keep from being overwhelmed but not enough to rid itself of the pathogen. By the time the animal reaches adulthood, it has a shaky balance with its protozoan parasites that allows it to live in reasonably good health while remaining a carrier. Babesiosis is still a serious threat to livestock in many parts of the world. In the United States it has been eliminated by a vigorous program of cattle dipping, which eradicated the tick vector. King Ranch manager Robert J. Kleberg is credited with building the first dipping vat in the state. Before the disease was eradicated in this country, nonimmune American cattle were protected from it by elaborate federal quarantine laws separating southern cattle from others in railway cars and stockyards. Northern cattle imported to the South for breeding purposes could be immunized by receiving injections of small amounts of blood from infected animals. Mark Francis of Texas A&M was a pioneer in the development of this method of immunization.

A cow moves through the Dipping Vat, while the man marks that the cow has been dipped, circa 1920s. Image available on the Internet and included in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

Covid, Flu, and Bird Flu today use the same PRCP test, done only in the Federal Government labs. One test per three very different diseases. Controlled by the Biden regime. Get the picture? Steve Kirsch, Meryl Nass have proven these are fake. One Texas Vet did her lab test. She didn’t find a Pathogen.

Human Liver #2, Johns Hopkins. See much difference? Covid Liver.

Still trust your government? I don’t. Robert Yoho taught me not to trust, Butchered By Heathcare, Pharma & Government. If you do you are a Fool.

That was an interesting and educational post. Thanks Abigail!